Was the Early Church Meeting on Sunday? A Fresh Look at Acts 20:7

Many Christians point to Acts 20:7 as evidence that the early church had already shifted to Sunday worship:

“On the first day of the week, when the disciples came together to break bread…”

It seems simple enough. First day of the week equals Sunday, and “breaking bread” equals a Sunday service. But a closer look at the text, Luke’s details, and Jewish customs of the time suggests a different picture.

How Days Were Really Counted

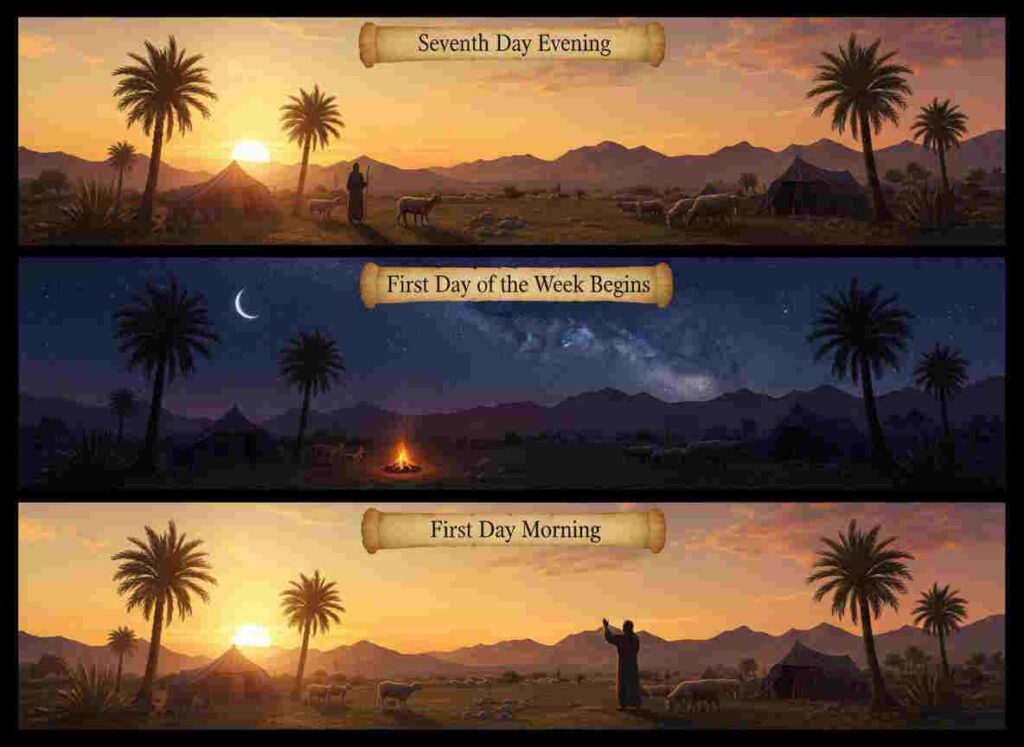

Today, most of us think of a day as running from midnight to midnight. Under that logic, the “first day of the week” naturally starts Sunday morning. But that’s not how a day was measured in biblical times.

From Genesis onward, a day begins in the evening. Genesis 1 repeatedly says, “And there was evening, and there was morning—the first day.” annual Sabbaths (holy days) followed the same pattern: the Day of Atonement and Passover both began at sundown. First-century Jews, including Pharisees, Galileans, and likely the earliest Jewish believers, all reckoned days this way. So when Luke writes “the first day of the week,” he likely means Saturday evening, immediately following the Sabbath — a conclusion that becomes clearer when we examine the details Luke himself provides..

Breaking Bread Late at Night

The phrase “breaking bread” can at times refer to a religious observance, such as Passover. However, Luke has already anchored the timeline by noting that Paul departed Philippi after the Days of Unleavened Bread (Acts 20:6), placing Passover roughly two weeks earlier. In Acts 20:7, “breaking bread” therefore appears to describe a shared evening meal rather than a festival observance. Luke’s narrative also provides several clues that this gathering took place at night:

- Many lamps lit the room, suggesting an indoor evening meeting.

- They were breaking bread and conversing until daybreak — something we can all relate to: gathering with close friends, eating, and talking late into the night.

- A young man named Eutychus fell asleep in a window — again, pointing to a nighttime occurrence.

- Paul departed the next day, meaning the following morning.

Many signs point to a night gathering, and with the understanding of a day starting at sunset this would be a Saturday-night gathering from our understanding, not a daytime Sunday meeting.

What “The Next Day” Really Means

Luke uses the Greek word ἐπαύριον (tē epaurion), which literally means “the next daylight hours.” In Luke–Acts, this phrase almost always refers to the following morning or daylight period, not a literal 24-hour calendar day.

So in context: Saturday evening meeting → midnight conversing → daybreak → Paul departs Sunday morning. Interpreting ἐπαύριον as Monday would stretch the story unnecessarily and contradict Luke’s narrative cues.

A Tale of Two Timelines

Consider two ways of reading Acts 20:7:

Sunday-daytime / Monday departure:

- Disciples gather Sunday morning

- Paul preaches all day and late into the night until the next morning

- Eutychus falls asleep

- Paul departs Monday morning

Problems: a 24-hour preaching session, ignoring night markers, and “next day” becomes Monday — a forced and implausible timeline.

Natural Saturday-night timeline reading (Approximate)

- Saturday sunset (~6 PM): Sabbath ends; first day begins

- Saturday evening (6–9 PM): Disciples gather, share a meal, Paul begins speaking

- Late night (~9 PM – midnight): Paul continues; Eutychus falls asleep

- Midnight → early morning (~12–6 AM): Paul continues until daybreak; lamps still lit

- Sunday morning (after sunrise): Paul departs Troas — “next day”

Saturday night, not Sunday morning, was the setting for this pivotal gathering. This timeline fits naturally: the evening meal, lamps, nighttime sleep, and departure all align perfectly with Luke’s account and Jewish day-reckoning.

Why This Matters

One important distinction should be made here. This reading does not assume that Acts is issuing mandates about worship days. If a shift in weekly worship practice were intentionally underway—especially one affecting both Jewish and Gentile believers—that is precisely where we would expect some level of clarification. Acts 20:7 does not provide that. It describes a gathering, not a mandate.

Read this way, Acts 20:7 points to a Saturday-night gathering that reflects how early Jewish-Christian practices were still rooted in Sabbath observance and sunset-to-sunset timing. Reading it instead as a Sunday-morning service arises from modern assumptions about how days are reckoned, not from the details Luke supplies.

This subtle but significant distinction reminds us that context—cultural, historical, and linguistic—matters. Attending to that context not only clarifies Acts 20:7, but also helps us read Scripture on its own terms, within the world in which it was written.